Let’s assume we’re in agreement- all this time we’ve been doing it wrong. How do we do it right? Let’s do two things to start out. Let’s set some goals, and let’s break this down into two parts: viewing the painting or print, and making the capture.

Viewing the Art

The lighting used for viewing the original painting, or the final reproduction, is probably the facet of the process that we have the least control over. Once the print leaves our hands (or, for that matter, the painting leaves the hands of the artist) we really don’t have much to say about how it is displayed or lit. Museums and galleries have some very tough challenges lighting work in a practical way. As we’ve seen, this can be critical in how the print is perceived and interpreted. There are, however, a few things we can do to establish attainable goals. Simply, we can reproduce the painting as faithfully as possible, matching the color and contrast to the best of our capabilities and within the limits of our equipment.

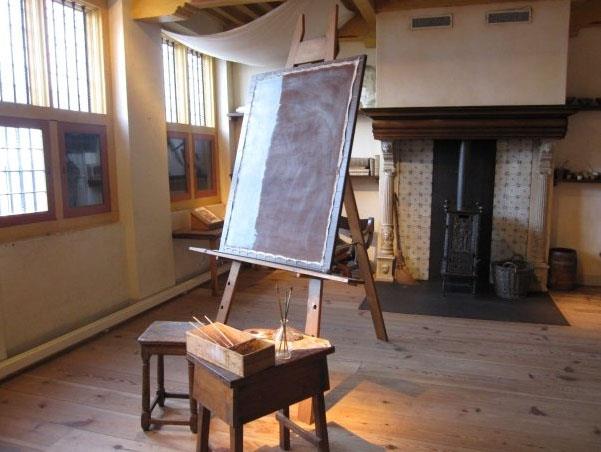

One of the keys to achieving that is to view, and match, the original paintings and the proof prints under lighting that is as close to the artist’s studio as possible. If the original was created in a North-light studio we’d prefer to evaluate our prints with lighting that comes as close as possible to the quality and wavelength of North light. Likewise, if the artist works with halogen spots trained on the work, we should view the prints with light that is the same- gallery-style halogen spots. The reasoning behind this is that every pigment or dye reflects light in a characteristic way. Paint will look slightly different than our printer’s ink under quartz lighting and North daylight. It may be dramatic, or subtle, but to get as close as possible to experiencing the vision of the artist, you need to view and match your final print under the same light that the artist used, with the original work lit identically. Only then can you really claim the print is faithful to the original.

Lighting and Capturing the Original

Let’s start with the most difficult goal. Let’s think about how we’d light and capture the painting as the artist saw it. The key to this is to recreate the light in the artist’s studio, down to the last detail. Bear with me… this is far from practical, but it’s a good exercise in understanding what the challenges are.

We would have to map out the location and size of the windows in the artist’s studio, and recreate them in the photo studio. This includes size, distance from the painting, height, angle… and would mean we’d either have to create light sources from daylight-balanced continuous, or strobe light sources. Remember, the wavelength, or color, of the light source is critically important to assure we’re reflecting the colors of the original correctly. The background walls are equally important. In Rembrandt’s studio we saw background walls with a warm tone. This will effect our “fill” light- the light that illuminates the shadows in the painting, such as under the brush strokes. The “main” light provides our primary color balance and illumination. The “fill” light provides the background light, illuminating (or contaminating, if you will) the areas not affected by the main light.

In essence, we’d have to build a complete “set”, like a movie or stage, of the artist’s studio with our artificial light.

Suppose, for a minute, that we could simply bring our gear into the artist’s studio and photograph it with the very light the artist used. This is certainly possible, but there’s one technical issue- the intensity of light in a North-light studio. Although sufficient for painting, the level of light a North-light studio is at the very lowest levels necessary for making a good camera exposure. This affects everything from color mapping to resolution. The more we have to amplify the sensitivity of a digital camera, the less we get in terms of resolution and true color fidelity. The actual studio is simply not bright enough.

So let’s scale back our goals a little, and try to simply get closer to what the artist saw than the standard copy practices. We are looking for soft side and top-lighting with an open shadow. Again, we can do this with a very large bank of strobes or continuous daylight balanced lights with diffuser panels (such as soft boxes), approaching the size and position of the original studio. They have to be a fairly good distance from the painting to assure even coverage of the work. If they’re too close, you’ll see variation in the light intensity from one side or another, or from top to bottom. When you move the lights further away you compensate for how fast the intensity drops off over the distance from the closest part of the painting to the furthest. (For more explanation of this, see this link on the Inverse Square Law.) The rub is that, again due to the Inverse Square Law, as you move the lights further away, the intensity drops dramatically. To use large banks of lights at the same distance as the original windows you’re going to have to pump huge amounts of power into those lights.

Or, you could use the Cruse Synchron capture system. Because the Cruse system uses banks of daylight balanced florescent bulbs, the spectrum of the light source is as close as possible to the North-light studio. Because it’s an inherently soft light source, it allows us to reproduce the softness of the light in the studio. Because we can control the light direction and intensity, we can accurately simulate the light quality from a variety of studio environments. …all at the push of a button.

Once again… the secret of the Cruse? It’s the lighting.