(Sign up here to receive ParrotTalk News in your email- bi-monthly, and we never share our list. Ever.)

Stop the Presses! Huge Printer Rebates!

We were all ready to suggest you have a nice, relaxing set-down by the pool, when HP and Epson blew us right out of the water with a Battle-of-the-Rebates.

Epson offers up to a $1000 mail-in rebate on their wide-format printers, and Hewlett-Packard answers with up to a $2000 MIR. Whether your interested in HP or Epson, if you’ve been waiting to pull the trigger on a wide-format printer, now may be the time.

Epson has also introduced a few new models- the 3880, an update of one of the most popular 17″ printers made, and the WT7900- a 24″ printer with aqueous-based white ink printing.

HP has released the Z5200- a 44″ PostScript printer similar to their non-PostScript Z2100 models.

It looks like both Epson and HP are trying to drum up some mid-summer sales- it’s your chance to take advantage and save some big bucks! For details, email us at info@parrotcolor.com

NEW @ PARROT

Announcing… the ParrotTalk News!

In any normal day at Parrot we see and hear a lot of interesting tidbits and meet a lot of incredibly talented and unique people. We wanted to put something together to share with you… important news, profiles of our clients, announcements about events, openings, shows and other threads that can help, instruct and inspire.

So here it is, the first of the ParrotTalk News… our “Dog Days of Summer” issue. We’re putting together an issue once every two months, and our past issues can be viewed at www.parrotcolor.com/ParrotTalkNews. Have a seat next to the pool, take a long sip of a cool drink, and have a nice read… and we’ll be starting out with a profile of a fascinating artist- Jim Heck, working for Classic Playfield Reproductions…

Relax and enjoy!

ARTIST PROFILE

Jim Heck, Classic Playfield Reproductions

Jim Heck, Software Engineer by day, is a devoted fan of Pinball by night. Well, night, weekends, and every other moment he has to spare. You perhaps could say he’s a fanatic. Since a child, Jim has played, studied, and even collected pinball machines. He currently owns over 18 machines, more than a few of which he’s restored and repaired.

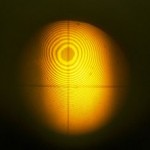

Jim’s obsession with pinball machines extends even to the unique, iconic art that adorns them. Jim, along with fellow artists at Classic Playfields Reproductions, carefully reproduces original vintage pinball art- called a “playfield”- to produce an illustration that stands on it’s own as a tribute to this slice of American popular culture.

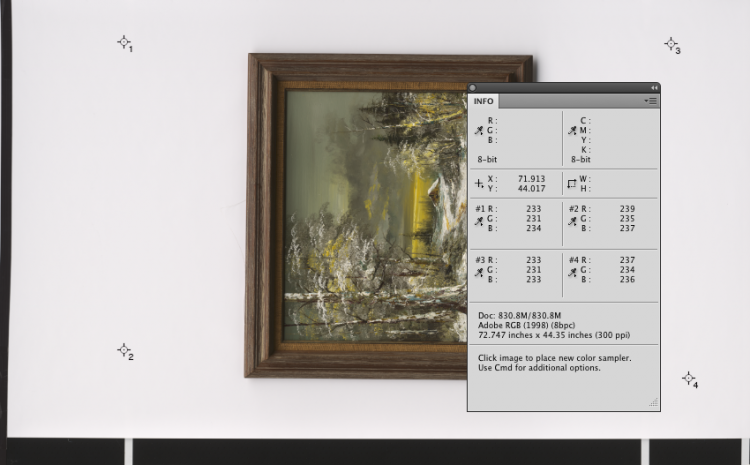

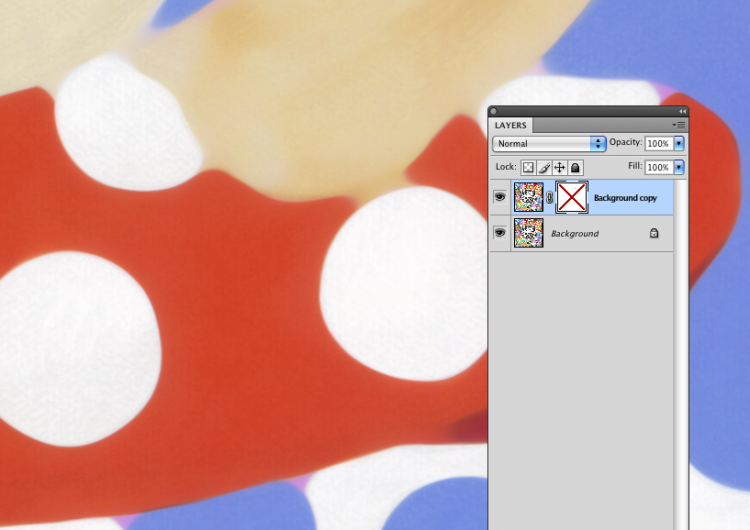

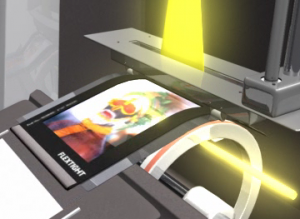

A few years ago Jim brought his playfield “Bally’s Flash Gordon”, (in his opinion possibly the greatest single-ball solid-state machine ever designed), for us to scan on our Cruse scanner. It was no easy task… the playfield is mounted a full 10 inches from its base fixture, not a normal configuration for the Cruse but well within it’s capabilities. (We had to do some Math.) It must also be lit evenly and scanned as completely geometrically true- not a problem at all for the Cruse. Jim then takes this ultra-high resolution scan into Illustrator and recreates every detail, sometimes needing to view the scan at as high as 6400% magnification. The result is something unobtainable using any other tool- a truly unique illustration. In the last month, Jim brought in his “Medusa” playfield- a wonderful work, and we can’t wait to see what he does with it. It will be a long wait, though… this stuff doesn’t go fast. Jim may spend ! hundreds and hundreds of hours on one playfield alone. That would be the definition of a “labor of love”, in our book!

To see more of the process and to hear Jim talking a little about his work take a look at the video we’ve posted on the ParrotTalk Blog, and you can see more of Jim’s work, and other Classic Playfield Reproduction artists at www.classicplayfields.com.

PARROT IN THE NEWS

David Saffir and Parrot/Angelica Fine Art Paper

Recently, David Saffir wrote about Parrot and Angelica Media on his blog:

“Those of us who make our own prints are, in many cases, constantly looking for that ideal combination of quality, price, and appearance in our inkjet papers. We’re lucky, in that our options increase daily, and competition keeps prices in check – if not driving them down at times!

“My good friends and colleagues John and Mark Lorusso, and Ted Dillard of Parrot Digigraphic (Parrotcolor.com) offer an interesting line of private-label inkjet papers. They’ve printed a number of my images for me on these papers – in color and Black and White – and the results have been impressive – so much so that I want to try them in my own shop.”

Read more here: New Testing, Inkjet Media From Parrot Digigraphic

Don’t miss David’s latest workshop, a once-in-a-lifetime Photo Safari with Infinite Kayak Adventures in February 2011, while you’re at his site.

COMING UP…

Get Ready for the Holidays!

OK, that wasn’t fair. I know, you just dropped your suntan lotion into your drink in shock… who wants to worry about the bustle of the Holiday season in the middle of August?

Well the truth is, if you’re in the business of selling Limited Edition prints or Fine Art Reproductions, there’s no substitute for planning ahead and leaving an adequate amount of time for production. Building up an inventory of the highest quality work- like Jim Heck reproducing his playfield art, takes time to do right.

Just do one thing… make a note to call us to discuss your plans when you get back from the beach. Then we can help you plan and budget your production, as well as your promotion, accordingly. Drop a line to info@parrotcolor.com, or call us at 978.670.7766- 321-775-4492 if you’re in sunny Florida.

TECH TALK

Which Printer Should I Buy?

Probably the second most common question we hear, after “Which monitor is the best?”, is “Which printer should I buy?” The answer, as usual, is, “It depends.”

We just had an interesting dialog with some folks from the Art and Graphics department of a major College of Art. We had the director of the Graphics Department here, accompanied by the “IT guy”… the fellow who would have to keep the machine, and the network running. They were confused- the advice they’d been getting from other Graphics departments in other schools was to go with Epson, yet the IT folks were recommending Hewlett-Packard.

We have considerable experience working with both systems, and interestingly, they both have very distinct advantages and disadvantages. One of the notable advantages of the HP “Z series” printers, however, is the combination of on-board printer and paper calibration, as well as a Postscript RIP built into the system. This, in particular, is an advantage for a printer in any Graphics Lab environment. Calibrating the printer, the standard papers or even exotic media and paper is one-stop-shopping. There’s no need for additional pricey calibration equipment, it’s built into the system and controlled from the admin workstation. Besides that, it’s top-notch quality- in the testing we’ve done it holds up to the standard of the industry, the XRite Spectrolino, very nicely, thank you!

The other big issue is job management, and again, the HP, with an onboard Postscript RIP, allows jobs to be fed to the printer simultaneously, stored, and queued as needed. If you’re in a lab and 7 students hit the “Print” button at the same time, the printer handles it- eliminating the need for a print server or addition RIP software. It allows you to manage the job queue from an admin workstation as well- allowing one workstation to manage several printers. Also, the onboard Postscript RIP allows you to process vector files- files from Illustrator, CorelDraw, InDesign, Quark or other illustration and page layout programs quickly and with the best quality result.

Epson printers enjoy huge market share- they’ve been at the top of the field for a very long time now…They certainly have a decided advantage if you’re printing a lot of sheet-feed pages, media that needs a straight feed path- like the Enhanced Matte Posterboard or extremely thick watercolor or fine art paper. But HP printers have come into their own. With comparable print quality, “quad-black” printing resulting in remarkable B/W print quality, efficient ink use, built-in calibration and Postscript RIPs, the HP printers are poised to find their rightful place in the market as a remarkably powerful tool- one especially suited for a multi-workstation “lab” environment.

Need help deciding which printer is best for your application? Email us at info@parrotcolor.com and one of our team members will contact you.

SPECIALS

Summer Specials on select Parrot and Angelica papers!

Take 10% off the regular price on any (or all) of these great media in our Product Showcase.

PRODUCT SHOWCASE:

Parrot Ultra Lustre Photo is a photographic quality “N” surface- a smooth, semi-matte with no distracting pebble texture or high gloss reflections. It exceeds the color gamuts of any paper available, with an extremely high reproduction of fine detail. It is the choice for traditional photographic reproduction.

Angelica Universal Photomatte is a pure-white matte surface photographic paper with the absolute highest gamut of any paper of this type. Available in single or double-sided printing, it’s one of the favorite choices of graphic design using full-color full-gamut images and true photographic printing.

Angelica Bright White Matte Canvas is a no-compromise canvas that surpasses any other canvas media available. We have developed our canvas media to match and exceed the performance of the best traditional photographic media. It is, quite simply, in a class all it’s own- and will change the way you think about printing on canvas.

Angelica Bright White Smooth is our premium watercolor paper for fine printmaking. A pure-white base with virtually no “tooth”, yet a true watercolor paper feel… It is a heavyweight stock that can even be deckled well. Bright White Smooth is the choice for a premium-priced print- whether of a photograph, painting or artwork reproduction.

To order, contact us today! info@parrotcolor.com