Art, for all arguments and discussions, is about expression. Artistic expression throughout history is as linked to the medium as it is to the artist. Even if we look back to prehistoric artists, making images of animals on caves in Lascaux, the work we see is a melding of the artist’s vision and the tools at hand. The beauty found in these primitive cave paintings is not only about the colors and forms—it is about the ability of the artist to express these forms, feelings, and sense of the subject using the simplest tools and pigments.

I have a favorite story about Pablo Picasso. The story goes that he was living in Paris, and for a while was short on money. He had developed a following, and he could sit down in a café and pay for his meal by dashing off a simple drawing with a pencil on a scrap of paper. Picasso was, among other things, a master of line. I can only imagine those sketches—I’m not sure if any survived, but I have been fortunate enough to see (and photograph for the collector) Henri Matisse’s personal collection, including some very personal drawings by Picasso, almost nothing more than doodles on the back of a finished work. They were beautiful in their innocence and simplicity, but also their expression. These works possess an undeniable mystery precisely because they are so compelling and expressive. Four simple lines on a piece of paper can elicit the beauty and mystery of the human form.

The black-and-white medium was the essence of photography for a very long time. It may be surprising to learn that the first known permanent color photograph was taken by James Clerk Maxwell as early as 1861—a mere 40 years after Joseph Niépce created the first photographs. It wasn’t until 1935—and the introduction of Kodachrome—that color became a viable, popular medium.

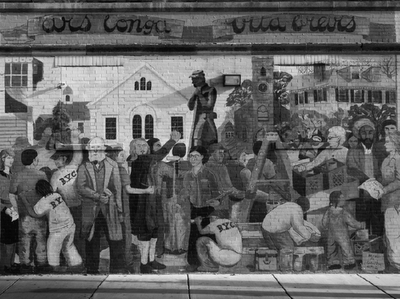

Black-and-white photographs as fine art are often distinguished as “expressive,” “sensitive,” and “creative.” Why is this? It is the limits of the medium and the photographer’s ability to work within those limitations to express a vision. Much of the power of a black-and-white image lies not in its representation of reality, but in its interpretation of reality at the hands of the artist.

And here is the first rub in photography: Photography, especially color photography, is commonly described as realistic. Colors are said to be “lifelike,” “true,” and “real.” An image is often trusted—and, I would argue, mistrusted—to be a representation of reality. Right there is the issue with photography as fine art: If a medium is reality, then how can it also be an expression of the artist’s vision?

By its very nature, black-and-white photography neatly skirts this issue. The fact that a black-and-white photograph represents colors with shades of gray makes it an interpretation, rather than a mirroring, of what the artist sees. It is the simplification of the palette and the limitations of the medium that give the image its power of expression. Take this one more step, into the world of digital photography. We now have a tool—Adobe Photoshop—that has almost unlimited power in producing images and effects that mimic and recreate “reality.” We are able to create photographs with as much color depth as our eyes can perceive and print them with a larger range of colors (or gamut), more than we ever could achieve in the traditional darkroom. We can record the world with astounding fidelity.

One of the beautiful things about digital photography, and the RAW file in particular, is that our creative process has shifted more to the act of combining pieces of an image rather than capturing the image, the negative, and working with what you’ve captured. I can make a digital photograph in color and reproduce it in color, black and white, or any other interpretation of that original image by manipulating the RAW file. Throughout this discussion of the various techniques and processes of digital black-and white photography, you’re going to have to decide exactly how much you want the medium to limit you, and how you’ll use that limitation to fulfill your vision. Whether you shoot in full color and control the image throughout the RAW process and subsequent image adjustments, or you use a camera that can only shoot in black and white (a “dedicated grayscale” camera), you will learn to harness its limitations.

It’s a decision you have to be aware of, learn about, and make for yourself.

(Excerpt from Black and White Pipeline – Lark Books)